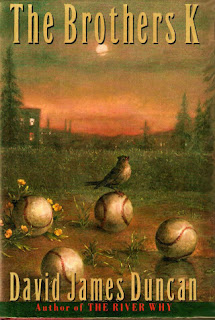

They gave cover designer Keith Hayes an order to come up with something that expressed the warmth of the novel but did not directly involve baseball. See what you think.

Hayes brought in covers that were rejected again and again. They finally accepted one that showed a man walking away through a golden field, but when they showed it to the author, he wanted it changed again.

Do you agree that the cover they finally settled on was the best one? I'm not sure why I like it, but I do. Perhaps red, white, and blue is suggestive of the American pastime. Perhaps the great white script set jauntily in the deep navy blue field suggests something nautical, Moby Dick-like, slanted as if the title was riding a wave.

Of course, the novel has many references to Herman Melville and Moby Dick. The name of the baseball team is the Harpooners, and their baseball uniforms have navy pinstripes. One of the main players is named Starblind, a counterpoint to Starbuck in the classic novel. There are lots of other literary allusions, some of them very subtle.

I much prefer my own design with the woman holding the book looking out across the baseball field, but probably showing anything zen on the cover was considered as taboo as a baseball glove by the marketing department. They did permit a subliminal "zen" in the Jonathan Franzen name at the bottom, the blurb underscored by a red marlinspike for emphasis.

Whatever the reason, the dustjacket now fits the content of the book for this reader. Like a glove.