See the child. He’s watching the baseball broadcast with his father, a former

pitcher.

I ask Papa if he ever doctored pitches. He says no. Then he says he may

have taken advantage of a drop of sweat or a nick now and again, but that sweat

and nicks are okay because they’re a part of nature. I was a nature-type

pitcher, Papa says more than a little lamely.

So Spit’s a part of nature too? I ask.

Just watch the game, he says.

On the television, Pee Wee Reese wonders aloud whether baseballs really get

doctored much. Dizzy Dean snorts and says the question is whether they ever

don’t.

--just a snippet of a hilarious account of a Pee Wee/Dizzy broadcast in

David James Duncan’s novel, THE BROTHERS K.

I thought of this when watching the Red Sox Broadcast the other day. They

were talking about a pitcher on suspension for the use of pine tar. One of the

broadcasters, a former pitcher, said that the use of pine tar always has been

wide among pitchers because it helps them grip the ball.

One of the other broadcasters pointed out that the rule says that no foreign

substance could be applied to the ball. The old pitcher (former player and Yankee broadcaster Jim Kaat) replied that pine tar

was not a foreign substance at all, but was made in South Carolina.

Can’t help laughing.

Speaking of baseball books, I recently read DAMN YANKEES: TWENTY FOUR MAJOR

LEAGUE WRITERS ON THE WORLD’S MOST LOVED (AND HATED) TEAM, edited by Rob Fleder.

There are pieces by Roy Blount, Jr., Pete Dexter, Daniel Okrent, Colum McCann,

Bill James, and many others.

I like the quote from David Rakoff:

“I hate baseball because of the lachrymose false moral component of it all,

because it wraps itself in the flag in precisely the way the Republicans do and

takes credit for the opposite of what it really is.”

“Baseball–and by baseball I mean its codifying straight-guy interpreters, its

bloated Docker-clad commentariat–traffics in that same false nostalgia, fancying

itself some sublime iteration of American values, exceptionalism, and purity

when, in fact, it’s just a deeply corporate sham of over-funded

competition…”

Especially the Yankees, “the apotheosis of Eminent Domain and rapacious

capitalism.”

The essay I enjoyed most was Pete Dexter’s “The Errors of Our Ways.” Wow,

this man can write!

Sunday, June 24, 2012

Perhaps for just one shining moment: Authentic

The study of the life of the artist is usually disappointing, although it sometimes enhances the appreciation of the art itself, adding to the meaning, illuminating the process of creation. We usually prefer the legend, one reason we liked Cormac McCarthy better when he was still a legendary recluse.

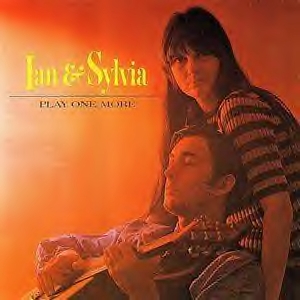

In their biographies and memoirs, the women of the folksinger era get higher marks in our estimation than the men. Carole King, Judy Collins, and Sylvia Tyson are more endearing than James Taylor, Bob Dylan, and Ian Tyson.

Still, I'm glad to have read these books, and I still enjoy a lot of the music from that time. Here's an interesting if rambling quote from cowboy/folksong artist, Tom Russell, from Four Strong Winds:

"Everybody thinks the folk scene was all namby pamby, nicey nice...but it was still competitive and there were people behind the scenes running it as a business. These songwriters were all trying to outdo each other and you had to have a lot of courage and guts, and a strong front if you were an insecure person. They were all trying to cut each other. People were vicious to one another, yet the public image was of all socialists and peaceniks. . .The competitiveness killed some of these guys. It was hard-core people playing hard ball. Survival of the fittest. You needed a tough shell."

There was of course the divide between the Beats and the traditional folk singers. Then the divide between the traditionalists and the commercial groups like the Kingston Trio and the Brothers Four. Then the divide between the traditional folk adherents and the people who wrote their own folksongs--a tradition started by Bob Dylan according to Ian Tyson and others, which suddenly created a headlong trend.

Whenever, however briefly, authenticity actually becomes popular, the Orwellian capitalists begin selling the appearance of coolness, false images quickly repackaged and mass marketed. The authentic then become less easy to see because of all those phony chameleon look-a-likes who keep changing in order to maintain the appearance of coolness, as marketed by Hollywood and Madison Avenue.

In their biographies and memoirs, the women of the folksinger era get higher marks in our estimation than the men. Carole King, Judy Collins, and Sylvia Tyson are more endearing than James Taylor, Bob Dylan, and Ian Tyson.

Still, I'm glad to have read these books, and I still enjoy a lot of the music from that time. Here's an interesting if rambling quote from cowboy/folksong artist, Tom Russell, from Four Strong Winds:

"Everybody thinks the folk scene was all namby pamby, nicey nice...but it was still competitive and there were people behind the scenes running it as a business. These songwriters were all trying to outdo each other and you had to have a lot of courage and guts, and a strong front if you were an insecure person. They were all trying to cut each other. People were vicious to one another, yet the public image was of all socialists and peaceniks. . .The competitiveness killed some of these guys. It was hard-core people playing hard ball. Survival of the fittest. You needed a tough shell."

There was of course the divide between the Beats and the traditional folk singers. Then the divide between the traditionalists and the commercial groups like the Kingston Trio and the Brothers Four. Then the divide between the traditional folk adherents and the people who wrote their own folksongs--a tradition started by Bob Dylan according to Ian Tyson and others, which suddenly created a headlong trend.

Whenever, however briefly, authenticity actually becomes popular, the Orwellian capitalists begin selling the appearance of coolness, false images quickly repackaged and mass marketed. The authentic then become less easy to see because of all those phony chameleon look-a-likes who keep changing in order to maintain the appearance of coolness, as marketed by Hollywood and Madison Avenue.

Saturday, June 16, 2012

Happy Bloomsday, everyone!

Last year on this day, I reviewed my treasured copy of James P. Anderson's Finding Joy in Joyce: A Reader's Guide to Ulysses. I discussed the Bloomsday footrace here. I've linked to some James Joyce related fiction at this link, I discussed John Huston's movie of The Dead here, and my discussion of Adrian McKinty's The Bloomsday Dead can be seen at this link.

A review of Gordon Bowker's new biography of James Joyce is here.

Now we're up to date.

A review of Gordon Bowker's new biography of James Joyce is here.

Now we're up to date.

Friday, June 8, 2012

Games, Life, and Death: Jill Lepore, Insights Galore

Men are made for games, the Judge saith.

Cormac McCarthy's Judge Holden, that is. McCarthy is also famous for saying that books should be about life and death. Well, considering those two criteria, McCarthy should certainly enjoy Jill Lepore's new work of creative non-fiction, The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death.

The Mansion of Happiness was one of many board games invented by Milton Bradley, whose games figure prominently in the book along with the more ancient games upon which they were based.

The book follows the stages of Mankind, connecting humanity's notions of life and death in every chapter. Such as Aristotle's three stages of Man, with the cycles of mankind parallel to the cycles of an individual lifespan. I've already posted about Emerson's conception of the universal trinity at this link.

The author devotes a chapter to famous psychologist G. Stanley Hall, the inventor of our concept of adolescence who also held the idea that the life of a man parallels the life of Mankind--birth, childhood, adolescence, adult, then old age and death.

Jill Lepore's narrative extends those stages a bit, with a look at the search for the origin of the atavistic egg, and an afterward devoted to the search for a rebirth, for the hope of a resurrection in the material future. Throughout she draws amazing connections between the game and life itself, while giving us the history of the concepts that too many of us take for granted today.

The game board is our map. Along the way, we are treated to the histories of games, the abortion and right-to-life conflict, mother's milk, children's books, parenthood, the divide between property rights and human rights, eugenics, cryonics, and more, all told with plenty of verve and irony and insights galore.

With marvelous notes and a complete index. One of my top five books of the year so far.

__________

Last night, after blogging about this, I started thinking about what she quoted by Mark Twain and picked up my volume of his collected essays. I read a couple of them, including his take on patriotism as a religion, but I didn’t come across the work she quoted under any title:

“The Revised Catechism

What is the chief end of man?

A. To get rich.

In what way?

A. Dishonestly if we can, honestly if we must.

Who is God, the only one and True?

A. Money is God…”

In an endnote, she cites Mark Twain's piece in The New York Tribune, September 27, 1871.

Her history of games is very interesting, and the American versions of more ancient games always have a way of changing life’s goals into money, such as the Parker Brothers' Monopoly.

This got me to thinking about another game that I played in my youth which she does not mention. It was called CAREERS. I did a search on the net and found out from Wikipedia that it was created by science-fiction author and inventor James Cooke Brown and came out in 1955. The game’s objects were happiness points but you could choose to collect them through love or fame or money, and board positions were obtained through the role of the dice. It seems to me now that this was a fairer, better game than Monopoly, which I also played.

Wikipedia says that James Cooke Brown also invented a new logical language, wrote about computers creating work, invented a new type of sailboat, and wrote a science-fiction work advocating a different type of social system where, in the future, Mankind could at last achieve peace. His books are all out of print and command prices in the hundreds of dollars. He died on a sailing trip to South America at age 78.

Cormac McCarthy's Judge Holden, that is. McCarthy is also famous for saying that books should be about life and death. Well, considering those two criteria, McCarthy should certainly enjoy Jill Lepore's new work of creative non-fiction, The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death.

The Mansion of Happiness was one of many board games invented by Milton Bradley, whose games figure prominently in the book along with the more ancient games upon which they were based.

The book follows the stages of Mankind, connecting humanity's notions of life and death in every chapter. Such as Aristotle's three stages of Man, with the cycles of mankind parallel to the cycles of an individual lifespan. I've already posted about Emerson's conception of the universal trinity at this link.

The author devotes a chapter to famous psychologist G. Stanley Hall, the inventor of our concept of adolescence who also held the idea that the life of a man parallels the life of Mankind--birth, childhood, adolescence, adult, then old age and death.

Jill Lepore's narrative extends those stages a bit, with a look at the search for the origin of the atavistic egg, and an afterward devoted to the search for a rebirth, for the hope of a resurrection in the material future. Throughout she draws amazing connections between the game and life itself, while giving us the history of the concepts that too many of us take for granted today.

The game board is our map. Along the way, we are treated to the histories of games, the abortion and right-to-life conflict, mother's milk, children's books, parenthood, the divide between property rights and human rights, eugenics, cryonics, and more, all told with plenty of verve and irony and insights galore.

With marvelous notes and a complete index. One of my top five books of the year so far.

__________

Last night, after blogging about this, I started thinking about what she quoted by Mark Twain and picked up my volume of his collected essays. I read a couple of them, including his take on patriotism as a religion, but I didn’t come across the work she quoted under any title:

“The Revised Catechism

What is the chief end of man?

A. To get rich.

In what way?

A. Dishonestly if we can, honestly if we must.

Who is God, the only one and True?

A. Money is God…”

In an endnote, she cites Mark Twain's piece in The New York Tribune, September 27, 1871.

Her history of games is very interesting, and the American versions of more ancient games always have a way of changing life’s goals into money, such as the Parker Brothers' Monopoly.

This got me to thinking about another game that I played in my youth which she does not mention. It was called CAREERS. I did a search on the net and found out from Wikipedia that it was created by science-fiction author and inventor James Cooke Brown and came out in 1955. The game’s objects were happiness points but you could choose to collect them through love or fame or money, and board positions were obtained through the role of the dice. It seems to me now that this was a fairer, better game than Monopoly, which I also played.

Wikipedia says that James Cooke Brown also invented a new logical language, wrote about computers creating work, invented a new type of sailboat, and wrote a science-fiction work advocating a different type of social system where, in the future, Mankind could at last achieve peace. His books are all out of print and command prices in the hundreds of dollars. He died on a sailing trip to South America at age 78.

Sunday, June 3, 2012

Craig Johnson's LONGMIRE

Tonight (Sunday, June 3rd) at 10:00PM (Eastern) on A&E, the first of a

planned 10-episode series featuring Wyoming sheriff Walt Longmire will be shown.

The series stars Robert Taylor (The Matrix) as Longmire and Lou Diamond Phillips as Standing Bear. Phillips is well known for many roles including the Tony Hillerman adaptations. Others in the cast include Kattee Sackhoff (Battlestar Galactica), Cassidy Freeman (Smallville), and Amber Midthunder.

I have long touted Craig Johnson’s books, a genre series which is narrated in the first-person by Longmire, but I’m uncertain how this will translate onto the screen. His very literary Hell Is Empty was one of the best books of any kind I read last year and I reviewed it glowingly in this blog.

Most of the good things are the thoughts rattling around inside the sheriff/protagonist’s head, and a lot of it is when he is brooding alone on things. With other people, he tends to be understated and introverted.

Still, I’m mighty glad for the author. He’s a Wyoming family rancher writing stretchers which have become successful. Years before he became a novelist, we used to read his horse-training articles in various equine-related magazines. When he gives talks before book groups, he is funny and self-effacing while looking the part of his fictional character.

LONGMIRE seems well-cast and the novels deserve an honest production. If so, it might inspire other modern westerns with a sense of humor.

Novels featuring modern small-town western lawmen are a genre unto themselves, of course, and in this blog I've reviewed several of them including James Lee Burke's Rain Gods, the western mysteries of A. B. Guthrie, Jr., Jamie Harrison's The Edge of the Crazies, and Richard Hugo's Death and the Good Life.

I guess we should count Cormac McCarthy's No Country For Old Men, though McCarthy takes the genre format and turns it into a literary comment on the nature of man. The duality is the ruthless animal man Chigurh and his opposite Sheriff Bell, the ultimate compassionate man. The trinity is completed with Moss, the man torn between the two, between the light and the darkness.

Moss can take the drug money and leave a man to die in the heat of the Apollonian sun, but at night his conscience will not let him rest until he takes water back to the man, as if a glass of water would plug up the holes in him. The symbolic reading is the only way the novel makes sense, and it is the source of the novel's greatness.

You won't need a symbolic reading for Craig Johnson's novels until you get to Hell Is Empty. It will be interesting to see how they play that on screen.

The series stars Robert Taylor (The Matrix) as Longmire and Lou Diamond Phillips as Standing Bear. Phillips is well known for many roles including the Tony Hillerman adaptations. Others in the cast include Kattee Sackhoff (Battlestar Galactica), Cassidy Freeman (Smallville), and Amber Midthunder.

I have long touted Craig Johnson’s books, a genre series which is narrated in the first-person by Longmire, but I’m uncertain how this will translate onto the screen. His very literary Hell Is Empty was one of the best books of any kind I read last year and I reviewed it glowingly in this blog.

Most of the good things are the thoughts rattling around inside the sheriff/protagonist’s head, and a lot of it is when he is brooding alone on things. With other people, he tends to be understated and introverted.

Still, I’m mighty glad for the author. He’s a Wyoming family rancher writing stretchers which have become successful. Years before he became a novelist, we used to read his horse-training articles in various equine-related magazines. When he gives talks before book groups, he is funny and self-effacing while looking the part of his fictional character.

LONGMIRE seems well-cast and the novels deserve an honest production. If so, it might inspire other modern westerns with a sense of humor.

Novels featuring modern small-town western lawmen are a genre unto themselves, of course, and in this blog I've reviewed several of them including James Lee Burke's Rain Gods, the western mysteries of A. B. Guthrie, Jr., Jamie Harrison's The Edge of the Crazies, and Richard Hugo's Death and the Good Life.

I guess we should count Cormac McCarthy's No Country For Old Men, though McCarthy takes the genre format and turns it into a literary comment on the nature of man. The duality is the ruthless animal man Chigurh and his opposite Sheriff Bell, the ultimate compassionate man. The trinity is completed with Moss, the man torn between the two, between the light and the darkness.

Moss can take the drug money and leave a man to die in the heat of the Apollonian sun, but at night his conscience will not let him rest until he takes water back to the man, as if a glass of water would plug up the holes in him. The symbolic reading is the only way the novel makes sense, and it is the source of the novel's greatness.

You won't need a symbolic reading for Craig Johnson's novels until you get to Hell Is Empty. It will be interesting to see how they play that on screen.

The Coolness of Absolute Zero Cool; Book Collector's Magazine

Congratulations to Declan Burke for winning the Last Laugh Award with his novel, Absolute Zero Cool, which I reviewed back in September (at this link). The award was presented at the Crimefest Convention in Bristol, England (thanks to the Rap Sheet).

Not the first nor the last honor for Mr. Burke, who is now at the fore of the growing Irish Noir movement along with Adrian McKinty, John Connolly, Colin Bateman, and several other good ones.

________

The June issue of Firsts: The Book Collector's Magazine features the novels of Michael Connelly.

The last thing I read by Connelly was his brief but excellent preface to the Declan Burke-edited book of critical Irish noir, Down These Green Streets: Irish Crime Writing in the 21st Century.

I used to read Connelly's books as they came out. I enjoyed the first ones, but he lost me somewhere back in the 1990s when I began to consider him too politically correct and prone to stereotypes unawares--in spite of himself. After reading the article in Firsts, I've now determined to give his novels another try.

This issue also has an interesting feature on crime novelists Gar Anthony Haywood and Gary Phillips, neither of whom have I yet read, and there is a book-to-film feature on Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye. Excellent stuff.

Which reminded me of Richard Layman's article on The Maltese Falcon appearing in January Magazine. You can read it at this link.

You can't read everything, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp. It is a blessing to look on my shelves and see so many fine books I've yet to enjoy.

Not the first nor the last honor for Mr. Burke, who is now at the fore of the growing Irish Noir movement along with Adrian McKinty, John Connolly, Colin Bateman, and several other good ones.

________

The June issue of Firsts: The Book Collector's Magazine features the novels of Michael Connelly.

The last thing I read by Connelly was his brief but excellent preface to the Declan Burke-edited book of critical Irish noir, Down These Green Streets: Irish Crime Writing in the 21st Century.

I used to read Connelly's books as they came out. I enjoyed the first ones, but he lost me somewhere back in the 1990s when I began to consider him too politically correct and prone to stereotypes unawares--in spite of himself. After reading the article in Firsts, I've now determined to give his novels another try.

This issue also has an interesting feature on crime novelists Gar Anthony Haywood and Gary Phillips, neither of whom have I yet read, and there is a book-to-film feature on Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye. Excellent stuff.

Which reminded me of Richard Layman's article on The Maltese Falcon appearing in January Magazine. You can read it at this link.

You can't read everything, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp. It is a blessing to look on my shelves and see so many fine books I've yet to enjoy.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)